While the majority of the 1940’s and 50’s “true” crime comics stressed action, violence, and character studies, Jack Cole had a different take on the form, with stories that featured plenty of action but were driven by deep, dark, and disturbing psychological pain.

Though he only created 13 true crime stories, Jack Cole’s two Tommy gun bursts of creativity in this form, in 1939-40, and 1947-48, grazed the genre and left an indelible mark.

The American crime comic book genre is

often said to have begun in 1942, with the start of

Crime Does Not Pay, published by

Lev Gleason and edited by

Charles Biro.

Three years prior, starting in early 1939, Jack Cole wrote and drew 6 “true” crime comic book stories. These included:

While this body of work is probably too small to credit Cole with invention of the genre (consider also the numerous pulp-inspired crime comics of 1936-39) , which peaked in American comics in the late 1940’s and is still going strong to this day, I think it’s safe to say that Cole was certainly one of the co-creators of the “true crime” comic book genre.

By the way, the man who is usually credited with inventing the true crime comic book,

Charles Biro, worked shoulder-to-shoulder with Jack Cole at the

Harry “A” Chesler studio in 1936-39.

In 1939, Jack Cole also edited the historically important

Lev Gleason title,

Silver Streak Comics (named after the Pontiac Silver Streak car, which one of the publishers owned). While at Lev Gleason, Cole created, among others, the characters of Silver Streak and Daredevil.

In 1941, Cole left his editorship at Gleason to begin a long career as Quality Comics’ star writer-artist. Upon his departure from Gleason, none other than Charles Biro stepped into Cole’s shoes as editor. beginning his 16-year career with the publisher. Biro is noted for steering his titles away from super-hero fantasies towards what he called “illustories,” which were meant to represent more realistic and “true” events.

It is probably impossible to say for sure whether Jack Cole influenced Charles Biro with his early stories, or whether Charles Biro may have given Cole the idea when they worked closely together, very likely sitting next to each in various studios in Manhattan.

In May, 1947, Cole returned to both editing and crime comics when he put together two issues of

True Crime Comics (numbers 2 and 3 – there was no #1) for

Arthur Bernhard, the owner of Magazine Village and partner to

Lev Gleason in the time Cole worked as editor there (and also the gentleman who owned the Pontiac car that the

Silver Streak book was named after… perhaps because he hoped the book’s profits would help pay for the car!).

I imagine a lunch conversation at an automat between Berhard and Chelser going something like this:

Bernhard: I got an idea for a new series, capitalize on the crime craze.

Chesler: Yeah, now that the war’s over, super-heroes are on the way out.

Bernhard: I got the printing and distribution all lined. Even got a killer title, heh. Just need a solid guy to write and draw the comics and edit them.

Chesler: What about Cole? You know he came up with the crime angle a few years before Biro.

Bernhard: Yeah, I remember. Guy’s good, that’s for sure. But he’s got a sweet gig over at Quality.

Chesler: He’s starting to work with assistants now, like Caniff and Eisner and those boys do. If the price was right, he might go for it.

Berhhard: (puffing cigar) I could make him the editor, have him do his Jack Cole thing on one story in the book and then write and layout the others that his assistants could handle. Yeah.. could work. It would be fantastic to get Cole… he’d make one of the best comic books ever… I’d be able to buy a second Silver Streak!

++++++++

And so Cole did make some truly great comics for Bernhard. I’ve already shared probably the best story of the two books,

Murder, Morphine, and Me in an earlier post. Here is another story from

True Crime Comics #2, “James Kent.”

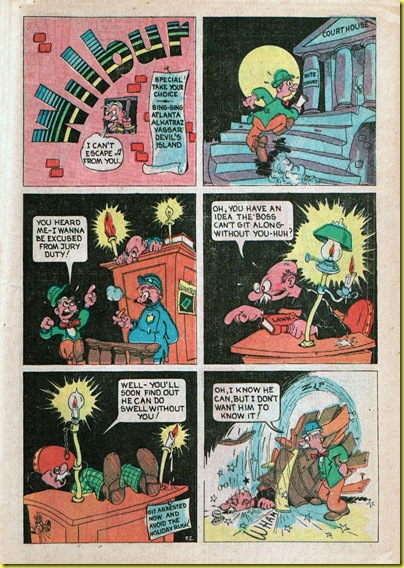

For the extremely short periods he worked as an editor, Jack Cole made a big mark with some nifty ideas. When he was an editor for Lev Gleason, he pioneered the idea of superhero cross-over stories, an idea which made Marvel Comics rich in the 1960’s. With True Crime Comics, Cole began the series with terrific idea, offering a cash reward for information leading to the arrest of the criminal depicted on the inside story. What kid, and even adult at the time could resist such a come-on? Cole bundled this brilliant, P.T. Barnum stunt into a stunning, eye-catching cover:

By the way, a Canadian reprint was issued a year or two later, with a partially re-drawn cover:

The cover is hardly an improvement, with a clumsy redrawing of Cole’s outstanding logo which brilliantly includes a black-and-white photo of a real policeman, enhancing the “true story” angle.

I did a little research, and could find no evidence of the criminal depicted in the story, and as far as I know, the publisher never published the winner of the reward money (if, indeed, it was ever awarded).

We do, however, get a terrific story that was written and partially penciled by Jack Cole (and most likely finished and inked by

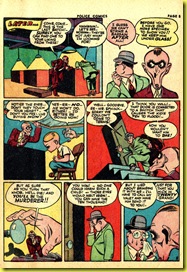

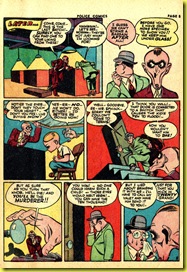

Alex Kotzky). The story leads off with a brilliant first page design using typography and iconic symbols to draw you into the story as both a reader and a sleuth… it’s impossible to look at this page and NOT read it.

One of the faithful followers of this blog (who has a

fascinating blog of his own which just published newly discovered underground sex art by Superman artist and co-creator

Joe Shuster ) has made me aware that Cole’s post-war stories often explore the dynamics of mob mentality, and the individual against collective society. In this story, a man commits an antisocial act – murder – which isolates him from his fellow human beings. For reasons unknown, however, James Kent is

already isolated and cut out of the pack before he murders:

Cole’s brilliance as a graphic storyteller shines through in this panel. There are 10 people shown in this one panel alone. They are organized into two groups (the Greek chorus in the bar and the rich dude and his sluts), and two individuals who stand as polar opposites: the law and the crook. The organization of these ten people, and the accompanying brilliant dialogue shows us (instead of telling, which would be boring) very clearly that James Kent is already ostracized from society by his poverty mentality and self-victimizing anger.

Part of the charm of Cole’s work was his ability to mix “bigfoot” cartooning with more “realistic” styles. In the panel above, the steam coming out from under Kent’s hat is a cartoony effect in an otherwise naturalistic drawing. This panel is also wonderful for the “Greek chorus” of barflies. Their dialogue (written by Cole) is terrific: “Oh boy! Free fuel!” Wonderful stuff. This aspect of the story is very similar to the rich, Saroyan-like characters that inhabit the bar in Cole’s

Angles O’Day stories.

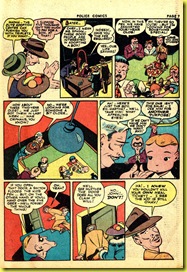

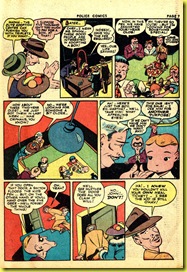

Of course, if it’s a Jack Cole story, then it’s almost always gonna have a sexy woman in it. In this, we get Sadie, a golddigger who later seems to redeem herself by astutely catching on to Kent’s scheme to unknowingly use her for an alibi. Cole’s depiction of Sadie has a vivid and disturbing quality to it, as though her callous and cruel treatment of Kent is somehow to blame for his crimes… because a man’s heart can only stand so much.

Much like Biro did in his crime comics, Cole uses a moralistic narrator. In this case, a cop, who allows us to vicariously experience the thrill of the crime and still feel insulated and ‘safe” from it. In the above tier of panels, note how Cole masterfully uses the 3 speech balloon tails to emphasize the reach of the “long arm” of the law. Also, note that in this sequence, the policeman’s dialogue transforms from reserved, scalloped-edged thought balloons to jagged-edged shouting speech balloons. That last balloon looks like a whirling buzz saw!

By the story’s end, even though he has escaped from prison, Kent has not escaped justice… because his own conscience and isolation from the world has become a living hell for him. By the end of the story, he cannot escape the eyes of society (and of God?).

Like every great artist, Cole used certain themes and elements over and over, perhaps unconsciously. About four years earlier, Jack Cole wrote and drew one of his best (and most disturbing) comic book stories, which appeared in

Police Comics #22 (Sept. 1943). It used the theme of eyes in an intriguingly different way. It was titled, appropriately enough, “The Eyes Have It.” Notice the similar use of eyes in the amazing splash from that story:

In fact, Cole makes the sweet eyes of a child (affectionately nicknamed Bright Eyes) the centerpiece of his Plastic Man story. The story has been reprinted in

Art Spiegelman and

Chip Kidd’s (sadly out of print) great book on Jack Cole and his work,

Jack Cole and Plastic Man: Forms Stretched to Their Limits. However, if you’ve never read this amazing Plastic Man story, one of Cole’s very best, then fasten your seat belt, and read on:

In both “The Eyes Have It” (1943) and “James Kent” (1947), eyes are used as symbol of how justice is achieved by shining the light of day on horrible secrets.

The 1947 James Kent story concludes with the words: “Eyes, eyes everywhere!” and the 1943 Plastic Man story concludes with the words: “Those eyes!” In one case, the eyes are revealing the truth about a murderer, and in another case,the eyes reveal the strength and courage of a sweet spirit.

In the 1943, the terrible secret involves heart-wrenching child abuse (a motif that crops up elsewhere in Cole’s work), and in the 1947 story a man is hiding the fact that he is a murderer and an escaped convict. Both stories hint at even deeper secrets. We don’t know why “The Sphinx” chooses to abuse his child. Indeed, his very name suggest an ancient secret., And, in the case of James Kent, we don’t know what earlier in his life history led him to the miserable, isolated state we find him in when the story begins. Is perhaps James Kent, “Bright Eyes” as an adult in the “real” world?

In any case, Cole’s work certainly embraced some dark aspects of the human psyche. While it’s obvious that Cole, who took his own life in 1958 for unknown reasons, must have had a secret or two of his own tucked away that will likely never be revealed, it’s no mystery that Cole was drawn to and fascinated by crime stories, inventing two ambitious crime series at the dawn of his career, years before the form took root. It could be argued that many of the stories in his famous super-hero series, Plastic Man, were as much dark crime stories as they were heroic journeys.

Cole only created one more true crime comic book story after the two issues of

True Crime Comics, a 10-page story about a rabid murderer in a bizarre, pseudo-modern modern West populated by cows and Cadillacs, (possibly an outtake from the True Crime series), which appeared in 1948, in

Western Killers #61 (Fox).

Much like his take on the horror genre, with his mid-fifties

Web of Evil stories, Jack Cole invested his crime comic book stories with a psychological bent, putting them years ahead of their time.

All text Copyright 2010 Paul Tumey