There’s a lot of cross-over between the careers and styles of Jack Cole and Klaus Nordling. “Thin Man,” one of Nordling’s earliest stories (from August, 1940) not only vaguely resembles Jack Cole’s work of the same period, but it also presents the origin of a character who can stretch his body, pre-dating Plastic Man by a full year.

From Mystic Comics #4 (August, 1940, Timely)

The story, when compared with Cole’s Plastic Man origin story from Police Comics #1, is a good illustration of both the similarity and the difference between the two men’s approaches. Both stories are solid and imaginative, but Cole started with a crook and made him go good, turning the superhero myth inside out and establishing a sly tone of satire and self-parody that made Cole’s Plas stories a cultural landmark.

By the way, the THIN MAN didn’t catch on and the character was gone by issue 5, appearing only once. (He was brought back in the 1970’s)

At his best, Nordling matches Cole’s nothing-held-back commitment to the story. Just as Cole’s stories can transport you to a world all their own, the best of Nordling’s stories – especially the longer ones - are equally atmospheric.

Klaus Nordling was a Finnish-American writer-artist who worked in comics from the 40’s through the 70’s. He broke in through Will Eisner’s studio, and became one of Quality Comics’ best writer-artists.

His best-known feature was LADY LUCK, which appeared in various Spirit sections, as a back up in various Quality comics, and eventually in its own title (here Nordling hit a peak with long, funny, off-beat stories and a personal investment that matches the way Cole wrote and drew Plastic Man and Woozy Winks).

For more information on Nordling, read the Wikipedia article on him.

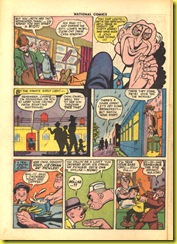

Nordling took over THE BARKER, the colorful feature in National Comics that Jack Cole and writer Joe Millard created (see earlier posts here and here) with the series’ third story. His style was similarly cartoony to Cole’s, and his sense of humor and imagination made him a natural to take a world Cole designed and flesh it out. He kept Cole’s character designs, right down to Col. Lane’s checkered vest. But he also layered on his own rich cast of oddballs.

Building on the Millard-penned BARKER story from National #43 (see here), in the fourth-ever Barker story, Nordling plays his own broadly comical riff on the mythical carnie story about a small town crook who tries to get the upper hand on the travelling carnival.

From National Comics 45 (Dec. 1944 – Quality)

The lisping, crooked mayor is particularly pungent in this story. Like Cole, Nordling built whole stories around strange, cartoony villains. Both men were likely heavily influenced in this by Chester Gould’s Dick Tracy stories, which splintered the human psyche into a bevy of bizarre bad guys.

Nordling wrote and drew BARKER stories from National Comics #44 to #67. In Autumn, 1946 the character got his own comic, starting with The Barker #1. Most of the 15-issue run was written and drawn by Nordling, although clearly other hands were involved. For over 30 years, each annual edition of Overstreet’s Comic Book Price Guide has listed Jack Cole as one of these hands. Here is the listing from the 39th edition of Overstreet’s:

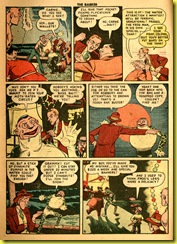

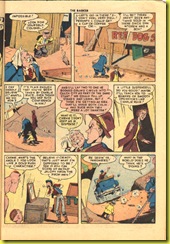

How poetic it seems that Jack Cole contributed the first and last appearance of this wonderful character. The lead story in The Barker #15 has a definite dark, psycho-comics Cole feel, as inky black dark waters literally drag the characters down. Also, there’s a drawing of a sexy drenched damsel that barks (if you will) Cole’s touch:

It’s unclear if Cole penciled the whole story and Nordling inked it. The inking is so black and unlike Nordling’s airy feel that I almost want to say that Cole is inking Nordling’s pencils! Why this would be, I have no idea. I actually think Nordling had nothing to do with this story and more likely one of Cole’s tried-and-true assistants, such as Alex Kotzky or John Spranger did a lot of the inking and finishes. I think it’s very likely that Cole wrote this story, as it has dark overtones, typical of his later work. See for yourself:

From The Barker #15 (December, 1949 – Quality)

It’s interesting to reflect that Jack Cole was probably ghosting here for a fellow artist who got into deadline trouble. The same thing happened with Cole when Plastic Man became a monthly comic and other writers and artists were brought in to meet the demand that Cole, as prolific as he was, could not keep up by himself. Perhaps there was a deadline crunch and Cole, always scouting around for more work, and the original artist, after all, may have been asked to help out in an ironic twist.

In any case, the way the extraordinary splash page (no pun intended!) works as both an intro to the story by showing a vignette of the climax and as a kind of symbolic picture of the power of the sub-conscious, suggests that Jack Cole wrote and drew this story. In this respect, the story feels very much like Cole’s multi-level Web of Evil stories of the early 1950’s.

The note at the bottom of the above Overstreet’s entry for The Barker is intriguing: “Cole art in some issues.” I’ve scoured several issues of the Barker and one story does stand out for it’s dark atmosphere, jam-packed story, and general weirdness. I think it’s a lost Jack Cole gem.

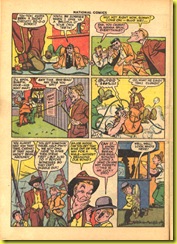

from The Barker #6 (Winter, 1948 – Quality Comics)

Why these two stories are signed by Klaus Nordling when Cole worked on them is a mystery. Perhaps there’s a clue in this quote from Quality editor Gill Fox about Nordling:

“Nordling was a little guy. Good-looking. And involved in local theatre. He had a very vivid imagination and was a good writer. In later years I'd send some work in his direction. But if you did something for him, he'd think you wanted something back. We got to know each other socially, but he still mistrusted people. Even me.”

Perhaps there had been a promise to Nordling to “brand” the Barker stories with his name as he built a career. Or, perhaps the editor of the book wanted to avoid conflict. Or… perhaps I am wrong and this is all the work Nordling, but after studying the comic book stories of Jack Cole intensely for the last eight months, these stories feel like Cole to me, even though it’s hard to be 100% certain.

This is a pretty clever story, you’ll probably agree. I think there’s a case to made for this being a Cole script and pencils with Klaus Nordling providing the inking and finishes. Just the imagery of the carnival setting up on the side of hill in front of a deserted ghost town alone is enough to convince me. Here’s yet another of those weird, veiled stories in which Cole’s sub-conscious seems to be saying something is not right. I get this sense very strongly in the beautifully cinematic night-time scenes, like this one:

We also get Cole’s core theme of shape-changing when Carnie Callahan (The Barker) disguises himself as a western owl hoot. And there’s the doppelganger theme that Cole toyed with throughout his career, when the performers of one circus go to battle with their alter egos who work for the rival circus.

The pacing, the richness of ideas, and the sheer quantity of ideas feel very much like a typical overstuffed Jack Cole story. In fact, this story is really quite a lost gem. The old western towns have a palpable presence. When you read the story, you can feel the “Cole magic.”

Whenever Cole set a story in the old west it was always vivid. Perhaps that’s due to his own vivid impression gained by biking through the western desert of the United States when he was only 18. See my article about his epic bike trip here.

The story also has several instances of some of Jack Cole’s oft-used graphic devices, or “Cole-isms,” as I call them (see here). One such Cole-ism is depicting a crowd in a very interesting way in which each person is more realized than a comic book artist of this era would typically bother with. You can see this in the night-scene panel above.

Also silhouetting the tents, banners, and circus roustabouts is very typical of Cole’s work. Lastly, his use of a full moon in story, 5 times times by my count, is something Cole’s drawings are filled with.

This is a very special story. In this story, Cole returned to his earlier style and also recovered, for the span of these 14 pages, the youthful exuberance and astonishing energy of his best early 1940’s graphic narratives. This story feels like the early MIDNIGHT, QUICKSILVER, and PLASTIC MAN stories.

Jack Cole would soon hit a wall in comics, as he personally became burned out and as the industry changed rapidly and classified him as too old-school for their needs. He would become a major magazine cartoonist and then create his own successful syndicated newspaper strip (Betsy and Me).

But back in early 1948, Cole somehow brought back some of the style and energy of his early 1940’s work, and created a lost gem in the back pages of an obscure comic.

No comments:

Post a Comment