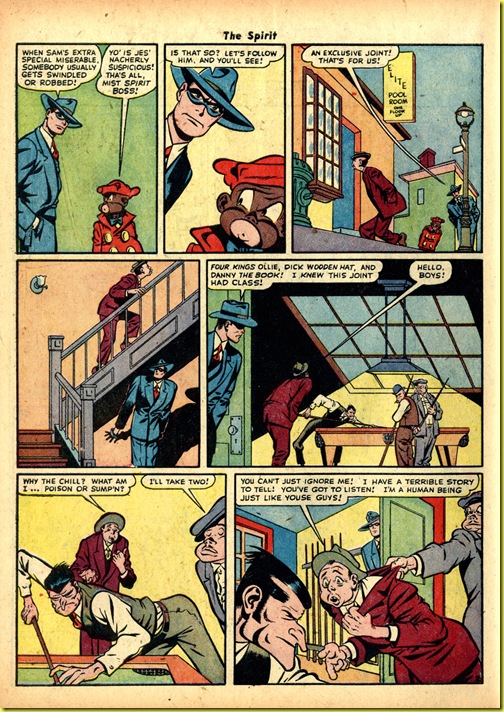

Cole ghosted THE SPIRIT for about a six-month period, writing and penciling (by my count) 17 stories. “Sad Sam’s Last Laugh” was also Jack Cole’s last Spirit. His Spirit stories, while carefully modeled after the patterns and look creator Will Eisner and first assistant Lou Fine had established, put more emphasis on both physical slapstick humor and death. This last story is remarkable enough to warrant a post of its own, for several reasons, which I’ll cover after you read this wild story, shown here in its 1946 reprint version from THE SPIRIT #5 (Quality Comics):

“Let US seriously contemplate suicide, too!” – chilling words to read, considering that Jack Cole took his own about 14 years after writing and drawing this story.

Suicide turns up over and over in Cole’s “comic” book stories. Although he often plays it up for laughs, there is nearly always an undercurrent of sadness. In this story, Sad Eyes Sam rather small-mindedly robs himself of his last day of life merely to cheat his fellow crooks. He accomplishes this by stabbing himself with a surgeon’s scalpel. Cole’s stories are filled with gruesome death and disfigurement, often creatively executed in bizarre fashion.

This story is also one of the earliest instances of what could be called Cole’s Grotesques. The faces of the criminal gang in this story are both comic and bizarre (page 3, panel 2 for example), in the best tradition of cartoonists such as Goya, Daumier, and Hogarth. It is not known that Cole drew upon any of the works of these artists for his own inspiration. We do know that Cole cited Chester Gould’s comic strip, DICK TRACY, as a major influence… and he may have gotten the idea of grotesque criminals from Gould.

In any case, this story features some excellent cartooning, even if the unknown inker did rob Cole’s lines of much of their life and spontaneity.

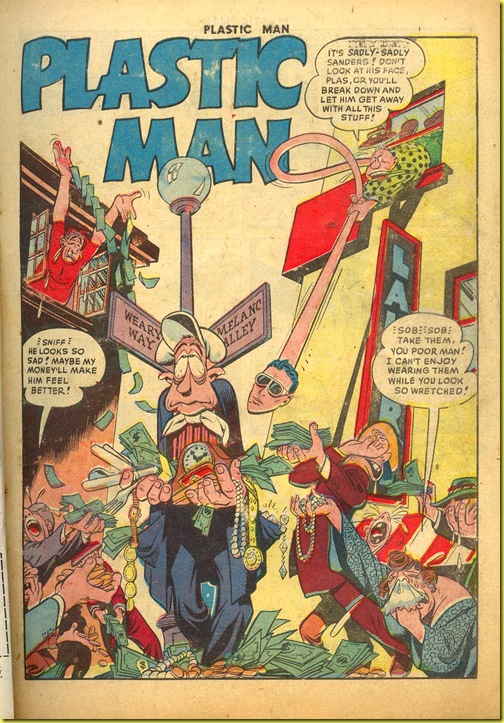

While Cole, like any great artist, returned to his themes and story settings over and over, this story is thus far the only instance documented in which he recycles a story concept. The character of Sad Eyes Sam would be reborn about 5 years later as Sadly-Sadly, in one of Jack Cole’s masterpieces, often reprinted, and shown here from it’s original appearance in PLASTIC MAN #20 (November, 1949).

It is interesting to compare the two stories to see how far Cole developed in just five years. The Sadly-Sadly story is nothing short of breathtakingly brilliant. Keep in mind, though, that Cole was ghosting on the Spirit story, and was obviously holding back to keep the stories looking and feeling similar to the “house” look well established for the wildly successful series.

The Grand Comics Database, a terrific resource and one which I’ve used heavily in developing this work on Jack Cole, lists Joe Millard as the writer for the Sadly-Sadly story. I found this hard to believe when I first read it. Having found this earlier version of the story by Cole, I have even stronger doubts that this classic story was written by anyone other than Cole. It’s too bad no records of who did what at Quality seem to exist.

From December 19, 1943 to June 25, 1944, Jack Cole ghosted 17 Spirit stories, by my count. After careful study of the Spirit Sections, here is my current, annotated, list of stories that Jack Cole wrote and penciled (they were inked by other hands, including Robin King):

12/19/43 – Death After Death

12/26/43 – Cloak and Coffin

1/2/44 – Killer Ketch (shapeshifting story)

1/16/44 – Ebony’s Inheritance (similar character shows up in other Cole stories, including Midnight Episode 18 , First Run)

1/23/44 – Murder By Magic

1/30/44 – Circumstantial Evidence (suicide, panel in story used as basis for Plastic Man splash)

2/6/44 – Radio Burglars

2/13/44 – Man O’ War

2/20/44 – In The Moorish Section of Central City

3/5/44 – The Charity Ball

3/12/44 – Double Eagle (Aztec Indian later used in Police Comics #75 story, “Case of the Ancient Clues”)

3/19/44 – Skelter and Crabb

3/26/44 – Torchy Tyler

4/23/44 – Rogoff (statue used in “Granite Lady” splash from Plastic Man, also lightning shock bolts used in later work)

4/30/4 – The Voodoo of Dr. Peroo

5/21/44 – Black Marx

6/25/44 – Sad Eye Sam’s Last Laugh (suicide, early version of “Sadly-Sadly” Plastic Man story)

Most of these stories can be found in the 8th volume of the SPIRIT ARCHIVES. This list is presented as a starting point, but it may change as I look at the stories with more attention.