Before PLASTIC MAN, MIDNIGHT, and THE SILVER STREAK, there was THE COMET, Jack Cole’s first superhero. Let’s turn back the hands of time and go nearly all the way back to the beginning of Jack Cole’s career, and practically the start of comic books in America themselves.

In 1936, Jack Cole moved from his hometown of New Castle, Pennsylvania to New York City, determined to jump start his career as a cartoonist. Like many penniless aspiring cartoonists in New York City at that time, Cole soon found work in comic books, which at that time were a brand new format that was taking off and needed new talent.

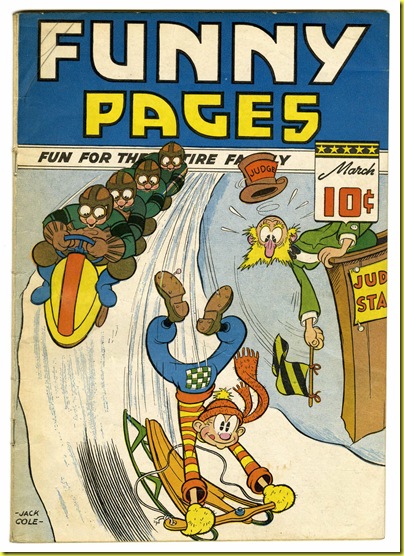

Cole started at the Harry Chesler shop, reporting for work at the shabby fourth floor studio of an old warehouse located on 23rd street (cited in Supermen! The First Wave of Comic Book Heroes 1936-41 by Greg Sadowski). His earliest comics for Chelser can be found in the 1937-39 issues of comics published by the small conglomerate of interests best-known today as Centaur. These pages are all light-hearted, jokey, humorous cartoons in the exaggerated, “bigfoot” style of gag cartoonists. Here is a signed example from Funny Pages Vol 3 #10 (Dec. 1939), a very are instance in which Cole acknowledges Christmas in his work:

You can see numerous examples of this earlier, funny material and read my articles about it here.

At the time, this style of comical imagery was what cartooning was widely considered to be, and exactly what Jack Cole had trained for as a student of the Landon School of Cartooning (see my earlier post here) correspondence course. Here is a prime example of Jack Cole’s early bigfoot style (note the graceful curve of motion and energy, an early indicator that Cole was a natural for drawing action-oriented images):

Funny Pages Vol. 3 No 2 (Centaur, 1939)

In April, 1938, Action Comics #1 appeared, bringing the first superhero, SUPERMAN, into the world and rapidly changing what comic books were all about. The issue sold out and was reprinted several times, ultimately selling an astonishing 200,000 copies (cited in Fire and Water: Bill Everett and the Birth of Marvel Comics by Blake Bell). In a few months, sales of SUPERMAN comics hit a half million copies of each issue, and that meant big money for the magazine’s publishers. Needless to say, plenty of other publishers and entrepreneurs saw a great opportunity and soon, superhero comic books covered the newsstands.

Like many of his fellow comic book creators, in 1939-40, Cole shifted from creating humorous gag-oriented comics to designing stories of heroic figures with superhuman abilities. Superheroes were taking off, and whole careers would be made for those lucky creators who could develop characters that caught the public’s interest (and dimes).

In late 1939, Jack Cole moved from Centaur to MLJ and created THE COMET, his first superhero character. At MLJ, he also created gag cartoons, humorous stories, and invented the movie-inspired comic book true crime story (a story-form that fellow Centaur alumni Charles Biro later developed into one of the most successful comic book lines ever for Lev Gleason publications). It was an extremely fertile period for this young, ambitious, enormously talented writer-artist.

It’s fascinating to study Jack Cole’s 1939-1940 work for MLJ (later known as Archie Comics). All the elements that would come together in the brilliant PLASTIC MAN stories are present in these earlier stories. In PLASTIC MAN, Cole would combine the three types of stories he created in 1939-40: humor, crime, and superhero. The result was a unique story-form that transcended the conventions of all three styles and, like a modern-day DON QUIXOTE (with Woozy Winks as Sancho Panza), became a timeless classic that continues to deliver a satisfying mix of thrills and smiles to new readers generations later.

But before he could achieve his killer combo in PLASTIC MAN, Cole had to master the form of the superhero story, and he started with THE COMET.

THE COMET is a bizarrely vengeful and blood-thirsty superhero, even by pre-comics code Golden Age standards. In the first story alone, he angrily melts criminals into “nothingness” and cheerfully drops a criminal to his death from several hundred feet in the sky.

A deadly disintegrating ray flows from his eyes all the time, and only by wearing glass goggles (glass paradoxically – and poetically – being the only substance that can block his death vision) is THE COMET able to protect innocent citizens.

A similar version of the goggled disintegrating ray concept appeared about two decades later, when Jack Kirby and Stan Lee created the character of Cyclops for The X-MEN. They also used another Cole idea for MR. FANTASTIC of THE FANTASTIC FOUR, who stretches like PLASTIC MAN. To my knowledge, neither Kirby nor Lee ever publicly credited Jack Cole with being the first comic book guy to come up with these concepts, therefore it seems very likely they arrived at these ideas independently of Jack Cole. However, the success Kirby and Lee had with these ideas is a testament of sorts to how brilliantly inventive Jack Cole was.

It’s also worth noting that Jack Cole’s more famous superhero character, PLASTIC MAN, also wears something over his eyes, in this case, sunglasses. It’s such a shame that Jack Cole was never interviewed about his comic book work.

Interviewer: Mr. Cole, why did you decide to adorn Plastic Man with shades?

Cole: I was always looking for little details that would set my characters apart, and make them interesting. My brother was visiting me and he had just purchased a pair of sunglasses at a drugstore on 53rd, and it hit me that having the eyes hidden and dark would let the reader imagine what the eyes looked like – and that would be a lot more compelling. Sort of like Harold Gray’s Little Orphan Annie. Plus, Plastic Man’s eyes were the one part of his body he couldn’t alter, so if he was going to be sure he could keep his identity a secret, he needed to hide his eyes.

Who knows what Jack Cole would have said if he were interviewed? A terminally shy man by all reports, perhaps he would have clammed up like the famous film director John Ford when interviewed by the well-informed, enthusiastic Peter Bogdanovitch near the end of his career:

Cole: I just did, that’s all.

Perhaps it’s just another facet of Cole’s obsession with face-changing. In any case, wearing shades adds greatly to the coolness of PLASTIC MAN, where THE COMET looks a little silly with his bathing cap and diving mask.

Though he may look silly when in costume, THE COMET is grimly serious when it comes to delivering justice. He isn’t content with delivering criminals to the police, who will deal with them. When face-to-face with a dirty thug, THE COMET lifts his glass visor and instructs the vermin to “PREPARE TO FACE YOUR MAKER!” This is one righteous crusader of justice!

His powers, as efficiently explained in the opening two panels of the first story (Cole’s typical full-steam-ahead fashion) are flight and heat vision. When studying the superhero characters of late 1930’s and early 1940’s comics, it is important to realize that they were all (mostly successful) attempts to cash in on the great demand for superhero stories that began with the first appearance of SUPERMAN in 1938.

Though THE COMET’S powers are derivative of SUPERMAN’S (who also flies and has heat vision – although I have yet to determine if Supes’ heat vision came before or after THE COMET –- anyone know?), Cole puts his own spin on them. THE COMET acquires his powers by scientific invention, a very common theme for Jack Cole. In fact, THE COMET’s power comes about as a result of a chemical introduced into his bloodstream, the same device Jack Cole used in the considerably more accomplished origin story of PLASTIC MAN, about a year later.

The rays that come out of his eyes are only deadly when they are crossed, making THE COMET perhaps the only superhero who is more powerful cross-eyed.

Cole wrote and drew the first four COMET stories, for Pep Comics 1-4. Here is the first of the four. Note the wonderful, well-designed splash page, a hallmark of Cole’s comic book stories. Note also the same graceful, energetic curve in the design that was also present in Cole’s “bigfoot” cover for FUNNY PAGES (above).

PEP COMICS #1 (MLJ – Jan,1940)

I love how, at the top of the third page in this story, THE COMET flies across the country on his back! The same playfulness found in Cole’s PLASTIC MAN Stories is found in these cruder, earlier stories.

********************************************

Jack Cole’s second COMET adventure is filled with wild invention, featuring a gang of crooks that terrorize the good citizens of Florida with blimps and light machines. I love the New York style skyscrapers that are magically transplanted to Florida. Cole was never that concerned with accuracy.

The imagery of the large, evil face in the sky is very similar to the images in Cole’s CLAW stories (some of which can be read here).

PEP COMICS #2 (MLJ - Feb, 1940)

********************************************

In his third COMET story, Cole – a student of the serial stories told in newspaper comics -- injects some continuity into his new series by carrying over the criminal mastermind from the previous story and bestowing him with a truly evil name: Satan!

This story features some of Cole’s most accomplished work to date, with the stunning page five standing out as one of the most effective pages of comic book work Jack Cole ever created! Vengeful destruction was rarely so graceful!

Pep Comics #3 (MLJ – March, 1940)

THE COMET was a perfect hero for Jack Cole, who excelled at depicting speed and graceful movement on paper. Cole’s stylized drawings of THE COMET zooming around the city so fast that his lower body is an elongated blur stretch towards the very same images he would use to great success in his PLASTIC MAN stories.

A terrific comic book artist, Jack Cole was also a great comic book writer. His work is so organic, it’s hard to separate his art from his writing. In fact, it seems he created his text and images all at once, a panel at a time, from start to finish. In this story, Cole the writer hits on the great concept of making THE COMET an outlaw figure. He keeps this continuity running in his fourth, and last, COMET story.

********************************************

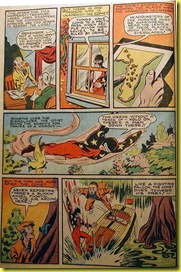

Pep Comics #4 (MLJ – April, 1940)

Cole is tightening his art and learning his craft in this story. Panels are more carefully ruled and his lettering is much improved. His art is tighter and his inking more accomplished. His large signature in the opening panel is a sign of how proud he must have been of this story.

Starting with a classic splash page, Cole delivers a knockout story. The grim nature of THE COMET’s world is further developed as our hero is attacked by an angry mob on page two. “Peaceful citizens gone mad,” THE COMET says, marking for perhaps the first time Cole’s continuing theme of the madness of human groups (a theme which appears in, among other stories, “Plastic Man Products” from Plastic Man #17, May 1949).

By the way, it is interesting to consider once again the similarities between the X-MEN’s shunned social position and THE COMET’s.

As further evidence that in THE COMET stories Cole was working out the concepts he would use in PLASTIC MAN, there is a startling similarity between the third page of this story and the second page of the first PLASTIC MAN story, from Police Comics #1 (August, 1941).

Both pages depict the fallen hero rescued by a wise, unselfish hermit-like figure. The layout and pacing of the two pages is almost identical. In Eel O’Brian’s case, the encounter leads to a spiritual transformation that is very quickly followed by a physical change. Part of the appeal of the Plastic Man origin story for me has always been connected to thefact that Eel O’Brian found salvation before he discovered he had super-powers.

In THE COMET’s case, the wise old hermit imparts a new social conscience to him, pointing out an injustice perpetrated not by a mad scientist or an easily identifiable crook, but by a business tycoon. It’s not Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle, but for comics of the time, it was a little subversive.

Cole’s penchant for morbid story elements comes through when THE COMET uses his disintegrating vision to rescue a trapped miner by apparently amputating his leg!

++++++++

Overall, Jack Cole’s COMET stories are great fun to read and have some stand-out visual moments and great splash pages. More importantly, from a historical perspective, these stories featured Cole’s very first heroic character and show him quickly working out his own unique brand of superhero, developing elements that would later be recycled in the creation of his landmark superhero character, PLASTIC MAN.

A personal note: I offer my apologies to my steady readers for the length of time between this and my last post. I have been going through some absorbing personal challenges. Also, I am running of out non-copyrighted Cole material to reprint! I do have some fun new articles planned though, so stay tuned!

All text copyright 2010 Paul Tumey.