This is the first of a three-part article providing a comprehensive look at comics master Jack Cole’s cartoons published in Playboy magazine in the mid- to late-1950s.

“You are so right about the comic mags being for the birds.”

- Jack Cole in a letter to a friend (quoted from Ron Goulart’s Focus on Jack Cole)

In 1945, to illustrate a story about him that was published in the Berkshire Courier, Jack Cole drew a self-portrait in which he is shown to be a gag cartoonist.

In this image, drawn when he was about four years into his already highly popular PLASTIC MAN comic book story series, and had established himself as one of the top comic book writer-artists around, Jack Cole chose to show the world at large that he was a magazine gag cartoonist. There is no trace of comics in this self-portrait.

By the way, the above self-portrait/illustration also works as a gag cartoon. The Joe Miller Joke Book shown in Cole’s 1945 cartoon refers to a famous collection of jokes (thought to be the first joke book) that was published in 1739 – so the joke here is that Cole is using some extremely old and stale jokes!

About 9 years later, Cole’s last comic book story, “The Monster They Couldn’t Kill,” was published in February, 1954. The comic book industry had changed from a booming business to a highly competitive field struggling in a shrinking market and fighting some extremely bad press. Cole left Quality Comics Publications, his creative home for over 12 years. It is rumored that he went to DC (National) and was turned down. After 3 weeks at Charlton (so far, it is not known what work, if any, Jack Cole did for Charlton), it appears he gave up on comics all together. Two months later, his first Playboy cartoons appeared, in the April, 1954 issue. Cole had a new career, and he never looked back.

About 9 years later, Cole’s last comic book story, “The Monster They Couldn’t Kill,” was published in February, 1954. The comic book industry had changed from a booming business to a highly competitive field struggling in a shrinking market and fighting some extremely bad press. Cole left Quality Comics Publications, his creative home for over 12 years. It is rumored that he went to DC (National) and was turned down. After 3 weeks at Charlton (so far, it is not known what work, if any, Jack Cole did for Charlton), it appears he gave up on comics all together. Two months later, his first Playboy cartoons appeared, in the April, 1954 issue. Cole had a new career, and he never looked back.

When Quality publisher Everett “Busy” Arnold tried to hire him back, Cole wrote to a friend that he had told Arnold no, saying he was going to become “the best damn cartoonist,” meaning gag cartoonist, not comic book maker.

There can be no doubt that Cole felt the world at large gave a slightly higher status to a magazine gag cartoonist than a comic book guy. One wonders how he must have felt privately, since even a cursory study of his comic book stories shows an enormous enthusiasm and personal investment.

It’s probably no coincidence that Jack Cole left comics in 1954, which was the same year that Seduction of the Innocent was published. The book, written a psychiatrist, condemned the comics of the 40’s as instruments of moral decay in American society and signposts to personal perversion for America’s youth. The book even used examples from Cole’s comics. For Cole, this must have been personally upsetting, to say the least.

Consider: a highly talented and optimistic small town youth transplants himself and his new bride to New York City to find a career as a cartoonist. He finds work in comic books, and pours his talent and energy into this new art form, actually inventing a part of it and making some of the most inspired examples of the form ever. After about 14 years of intensely hard work, his efforts are rewarded with public condemnation and no work. It’s no wonder that Jack Cole moved on.

Cole was a supremely creative person, and his re-invention of himself into one of the premier gag cartoonists of all time can be seen as an extension of his creative powers. Like his character, Eel O’Brian, who created a fun new career for himself as Plastic Man, Cole shifted his shape.

But it wasn’t an overnight transformation, even if it seemed to be.

In actuality, Cole had pursued a shadow career as a gag cartoonist all along. In the late 1930’s and early 1940;s, Cole sold a handful of cartoons to Boy’s Life, Collier’s and Judge, all top markets and national magazines.

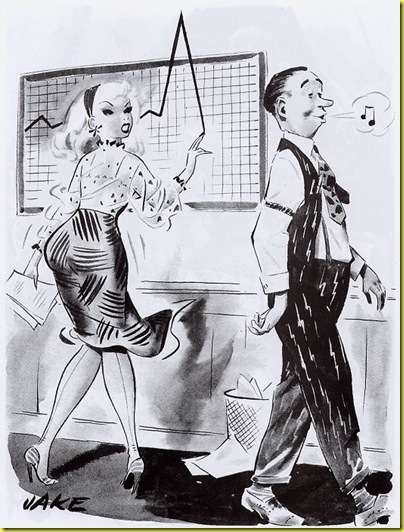

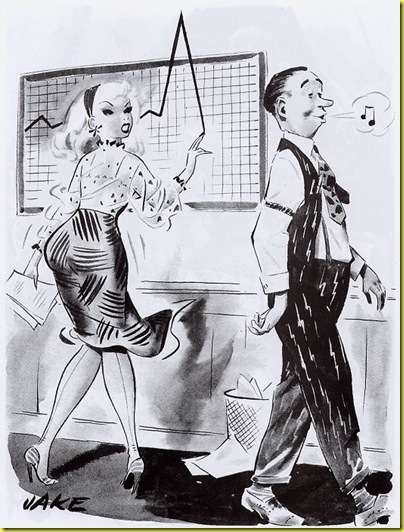

Since the mid-1940’s, under the pen name “Jake,” Cole had been selling sexy gag cartoons to the under-the-counter, digest-sized men’s magazines published by Humorama. Here is one, date unknown, that ran with the caption: “Let’s walk past the Y.M.C.A. and listen to the windows break!” :

Or, this one (again, date unknown), with the caption: “All right, you!”

More examples of Cole’s 1940’s sexy gag cartoons can be found in the excellent book, The Classic Pin-Up Art of Jack Cole, edited by Alex Chun. Online, more examples of Cole’s “Jake” cartoons can be found at the wonderful Pin-Up Files website.

In the late 1940’s, Cole’s comic book work dropped off for brief periods, while he concentrated on developing into a great gag cartoonist. He submitted to the highest markets and was summarily rejected. In 1956, in an article in The Freelancer, Cole reflected:

“I retreated to the minor class magazines (bless them all), where I should have started in the first place, and delved into the task of learning basic gag craft.”

Thus, throughout the late 1940’s and and early 1950’s, Cole’s attention was divided between his comic book career, where he was a confident, established, well-paid master and his developing gag cartoonist career, where he was a learner.

Cole probably saw the first issue of Playboy on the stands in December, 1953. Marilyn Monroe was on the cover. It was not a digest, but it was awfully thin, and the main story was a reprint of an old, public domain Arthur Conan Doyle Sherlock Holmes story, which suggested not much money was available for contributors.

Months earlier, responding to a trade journal ad, Cole had already sent some cartoons in (at that point,m the magazine was going to be called Stag Party). He was published in the fifth issue of Playboy, effectively getting in on the ground-level of a cultural phenomenon.

Years later, in an impassioned obituary that appeared in the November, 1959 issue, presumably written by Playboy publisher and friend Hugh Hefner, it was revealed “The first drawings he (Cole) submitted were rejected, but they carried a note back with them expressing considerable interest in his style and asking him to send others.”

In short order, Cole broke into the new magazine. And, it turned out that – public domain reprints aside – there was plenty of money available as Playboy quickly became one of the highest paying markets for gag cartoonists everywhere.

His first published cartoon for Playboy appeared in the April, 1954 issue.

First Published Jack Cole Playboy Cartoon, April 1954

One of the recurring themes in Jack Cole’s comic book stories is the interplay between youth and old age. In a 1940 HIGRASS TWINS episode (posted on this blog here), Cole drew comedy out of grown men being treated like babies. One of his last PLASTIC MAN stories, “The Fountain of Age,” (Plastic Man 23, May, 1950) played with age versus youth. In a way, this is merely another side to Cole’s fascination with shape-shifting, in that we all shift our shapes as we age. In this cartoon, Cole is drawing on one of his pet themes.

As we shall see, part of what makes Cole’s Playboy work great, and the equal of his best comic book work, is that it successfully draws, probably unconsciously, on Cole’s own themes and obsessions.

This was the start of a long run for Cole. Starting with Playboy’s fifth issue in April, 1954, he would have something in very nearly every issue until his death, about 5 years later.

Cole repeats the “old geezer and young beauty” motif in his next published cartoon, which is so well done that no caption was needed.

Playboy, May 1954

Just as his comic book stories were often packed with more jokes-per-square-inch than almost anybody else’s, Cole’s Playboy gags were also layered with multiple jokes and visual wit. In addition to the gag about using the stripper Torchy Dare’s g-string as a slingshot, there is also a sly visual pun with what will happen. The rhinestone-studded g-string will hit the phallic-rendered light bulb, causing it to explode, which is also a suggestion of what will happen sexually between the two people in the cartoon. Cole is playing with time in this cartoon, showing us the moment before the funny action, which heightens the humorous effect and results in a more vivid mental image.

By the way, the stripper’s name, Torchy, may be an in-joke reference to the sexy Quality comics character, TORCHY, who was drawn by Cole’s former editor at Quality and friend, Gill Fox.

Lastly, one can enjoy Cole’s lush wash and watercolor Playboy cartoons both for the style of illustration, which the publisher and editors found fascinating, and for the realization of feminine sexuality.

It was Playboy itself (and that probably means Hugh Hefner writing) that provided perhaps the best appreciation of Cole’s women. In the November, 1958 obituary referred to earlier in this article, they eloquently wrote:

“Nobody could draw a gorgeous girl with the gusto and loving care of Cole… those langorous, full-breasted, ample-hipped sirens with the sooty eyes, pouting mouths and deep-dish navels.”

In the next issue of Playboy, Cole had three cartoons, and began his famous FEMALES BY COLE series. This series was drawn in black ink and worked in beautiful contrast to his lavish full-page wash and watercolor cartoons. In FEMALES, the women Cole draws are not ravishing or sexy at all. In fact, their bodies are often fantastically altered, sometimes in startling and grotesque ways. This is wholly different kind of cartooning. Here is the first FEMALE BY COLE cartoon, which started out with a different series name: FEMALE SEX TYPES by COLE:

Females By Cole: 1

Playboy, June 1954

It’s really no surprise that Playboy and Jack Cole found each other. In addition to the publisher, Hugh Hefner, being a cartoonist himself, sex is a primary theme in all of Jack Cole’s work, including his comic book stories, which are filled with beautiful women and geeky men tripping over themselves to get at them.

With his FEMALES BY COLE series, Cole began to dig deeper into the psychology of sex. The original title of the series is an indicator of Cole’s intentions: FEMALE SEX TYPES. Now that he could work with the gloves off , and not be constrained with a young audience (although admittedly, Cole and his comic book publishers rarely seemed to consider the sensitivities of their young, impressionable readers), Cole approached the topic of sex as directly and honestly as any humorist ever has.

This series was designed to print smaller than his full-page cartoons, integrated into a page that had text on it. It may have been a savvy economic decision by Cole, as well, since producing the line art was very likely less work than the elaborate wash and, later, watercolor cartoons. Thus, Cole could sell at least two cartoons per monthly issue, which was the case from this point on. Cole created 52 FEMALES cartoons in all. From the start, the magazine got behind Cole’s series. Here is the announcement in the introductory “Playbill” page of this June, 1954 issue.

This series was designed to print smaller than his full-page cartoons, integrated into a page that had text on it. It may have been a savvy economic decision by Cole, as well, since producing the line art was very likely less work than the elaborate wash and, later, watercolor cartoons. Thus, Cole could sell at least two cartoons per monthly issue, which was the case from this point on. Cole created 52 FEMALES cartoons in all. From the start, the magazine got behind Cole’s series. Here is the announcement in the introductory “Playbill” page of this June, 1954 issue.

It’s a little disconcerting to imagine getting “Spinster” as a Valentine’s Day card. However, after studying the currently popular TV series Mad Men, which portrays the end of the 1950’s sexist man that Playboy both catered to and created (in the second season, the characters are sometimes shown reading Playboy magazine), it is easier to visualize Madison Avenue executives tickling each other with these sharp-witted cartoons. Today, people exchange funny sexual pictures via emails that make Cole’s cartoons like tame by comparison.

With his usual hit-the-ground running energy for a new direction, Cole also had not one, but two beautiful and funny wash cartoons in the June, 1954 issue.

Playboy, June 1954

Note the third occurrence of the older man and younger woman theme. After Cole was gone, Playboy reversed the theme and created a long-running series with a saggy-breasted, ancient nymphomaniac in a negligee.

The next issue of Playboy featured four Jack Cole cartoons, including a rare black and white brush work line gag cartoon that wasn’t part of his FEMALES BY COLE series:

Playboy, July 1954

Like his FEMALES series, this cartoon was designed to run smaller, inset into a text page with a two-column width. It’s almost a FEMALES BY COLE cartoon, since the woman is not gorgeous, and she is symbolically disfigured. Note also that Cole uses a different signature, with ‘COLE” in printed capital letters, instead of the cursive, brush- stroked “Jack Cole” of his wash cartoons, such as in this case:

Like his FEMALES series, this cartoon was designed to run smaller, inset into a text page with a two-column width. It’s almost a FEMALES BY COLE cartoon, since the woman is not gorgeous, and she is symbolically disfigured. Note also that Cole uses a different signature, with ‘COLE” in printed capital letters, instead of the cursive, brush- stroked “Jack Cole” of his wash cartoons, such as in this case:

Playboy, July 1954

A shy, milquetoast studies what must be one of the prostitute’s colleagues in action. He is walking home from the market, perhaps to his wife. The ridged, rounded form of a loaf of bread pokes out of a bag suggestively.

In the book, Forms Stretched to Their Limits: Jack Cole and Plastic Man, Art Speigelman notes that a surprisingly large number of Cole’s Playboy cartoons are about impotency and loss. The above cartoon is the first of these. It is both funny and slightly sad. One cannot help but think of Cole’s suicide when faced with work about impotency. As Playboy publisher (and Cole’s friend) Hugh Hefner has said, “the mystery of his death informs the work.”

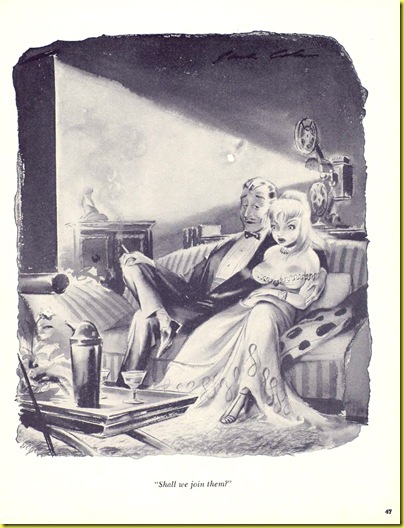

This next cartoon is unusual in that it’s an ink wash inserted into a page, like the black-and-white line cartoons. Even more interesting is that it’s a cartoon about male-to-male sex appearing in a magazine grandly celebrating heterosexuality.

Playboy, July 1954

The cartoon, signed “Jack,” is edgy enough with the inclusion of the words “God” and “damn.” This is probably why Hefner bought it, as part of his masterful broadening of what was acceptable in mainstream American culture. But, it seems to me that there’s another layer. The joke is that, instead of a domestic male and female reading and napping in a living room with the embroidered homily of “God Bless Our Home” hanging on the wall, we have two men in a prison cell with the homily expressing their feelings as “God Damn Our Home.” It’s my own reading that the men are indeed sexual, but more as a kind of substitute for the “real” thing, namely sex with a woman. The cartoon also resonates with how the average, married, domesticated American Male may have really felt about his home life, from time to time. Whatever the intended reading, this cartoon works on several levels.

The second Females By Cole made it into Playboy’s Table of Contents:

Females By Cole: 2

Playboy, July 1954

Playboy, August 1954

In the August, 1954 issue, Playboy provided a formal introduction to its stable of cartoonists. Note that Jack Cole is at the top, above such well-known cartoonists as Gardner Rea and Virgil Partch (VIP). Hugh Hefner has said that he wanted to develop his own cartoonists in the Harold Ross/The New Yorker model (such as with Peter Arno), and that Jack Cole was his primary “house-style” cartoonist.

Cole delivered a stunning cartoon for this issue, the original art of which has surfaced as is currently on auction (as of February, 2010) at the Heritage Gallery website here.

Playboy, August 1954

This is another moment, frozen in time. In just a moment, the two lovers will be lying on the ground, making love. Even though he has left sequential narrative behind, Cole is still occupied was how time works in comics and cartoons. For a fuller analysis of this cartoon, and a nice san of the original art, see my earlier post here.

Cole had a second full-page wash cartoon in this issue. This is a little different that his usual cartoon… the woman is not as voluptuous, and the joke is not centered on the man and woman connecting sexually. In fact, the cartoon is funny and vaguely disturbing at the same time. His composition feels like a comic book panel.

Playboy, August 1954

Females by Cole: 3

Playboy, August 1954

Note the recycling of the Y.M.C.A. concept shown in the earlier Humorama cartoon.

Cole had two cartoons in the September, 1954 issue. His full-page cartoon returns to his Nebbish archetype.

Playboy, September 1954

If the would-be voyeur was fat, and wore a polka-dotted blouse, and was named Woozy Winks, he’d fit right into this scenario. This skinny, gawky, none-too-bright fellow adorned with big round eyeglasses was also the way Cole drew himself in a few cameos in his comic book stories. Here’s a page from a 1944 INKIE story (see post here for full story):

Cole’s Female #4 is quite dramatic, but seems to resonate deeply with the virginal state of mind. Hugh Hefner called this series “psychograms.” Look at how Cole’s lively brushstrokes make the image jump off the page in contrast to the polished art on the adjacent page. His cartoon is the first thing you see in this spread. Cole was a design genius. We are probably very lucky that his considerable gift was never unleashed in advertising.

Females by Cole: 4

Playboy, September 1954

The October, 1954 issue devoted a full third of it’s letters page to Jack Cole’s cartoons. This also is the first (of many) reprinting of a Cole Playboy cartoon. Again, this was a deliberate step by Hefner and Company to establish Cole as the foremost cartoonist of the Playboy style.

This issue also presented Cole’s first full color gag cartoon, done in watercolor, instead of India ink washes. Sadly, the printing had not yet been worked out and this image was printed with the color plates slightly out of registration. Again, the shy, tall, gangly, round-spectacled man is no match for the sexual powerhouse that is a Cole female. I used to have a girlfriend that liked to invite me to have sex by calling it “checkers.” When I finally asked her why, she said, “because every time I move, you’ll jump me.”

Playboy, October 1954

Always inventive and intuitive, as well as a master designer, Cole fund a variation on his FEMALES format. The form perfectly fits the content. This would not have worked as a square layout; it needs the longer rectangle. Again, it is interesting to note how the bodies in this series are not at all the titillating eye-candy of the full-page cartoons.

Females by Cole: 5

Playboy, October 1954

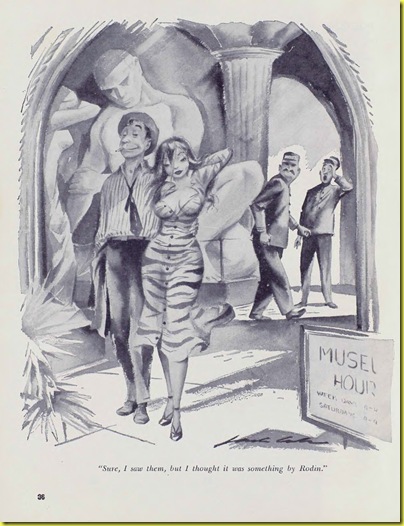

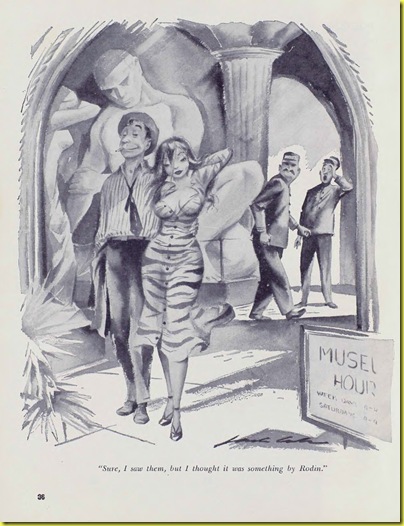

Playboy, November 1954

In other words, in the book, the characters were lying down, and probably not just kissing. It’s funny that this is observed by a rather frumpy woman. Cole is exploring women’s sexual fantasies as well as men’s.

In the above cartoon, Jack Cole introduces a new theme into his work: the differences and similarities between art and life. He played with this idea a little in an an early Plastic Man story (Police Comics #20, July 1943) in which the characters must find Jack Cole himself to solve a murder.

Females By Cole: 6

Playboy, November 1954

This one has two jokes… the cash register bed, and the “No Sale” to minors. It seems interesting that Cole would include a kiddie into this cartoon. Perhaps he was thinking about the condemnation some of comic book work received in Frederick Wertham’s book Seduction of the Innocent as being part of a general corruption of youth. It’s as though Cole is saying, “hey… even a prostitute like me has standards!”

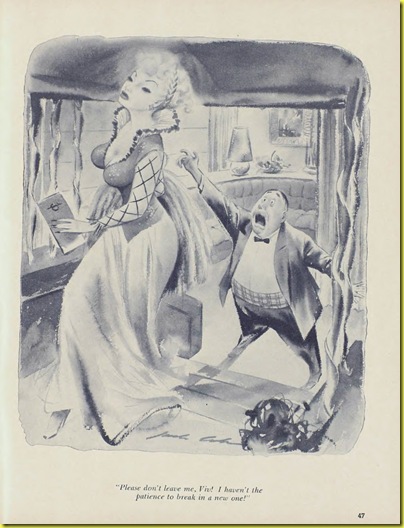

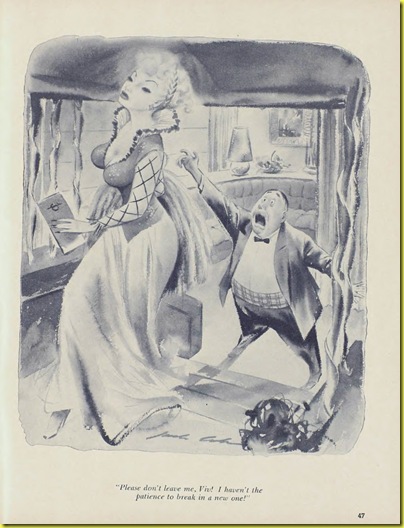

Playboy, December 1954

Again, it’s funnier to show the moments before or after the sexual act. In this cartoon, we must mentally rewind the scene a few moments backwards in time. This is also the first appearance of Cole’s tiger dress, which appears in later cartoons, too. Cole used patterns (see posts here) a lot in his comic book work and began to integrate them into his Playboy cartoons more and more.

Females by Cole: 7

Playboy, December 1954

Sex and death, all in one bizarre-yet-funny cartoon: classic Jack Cole.

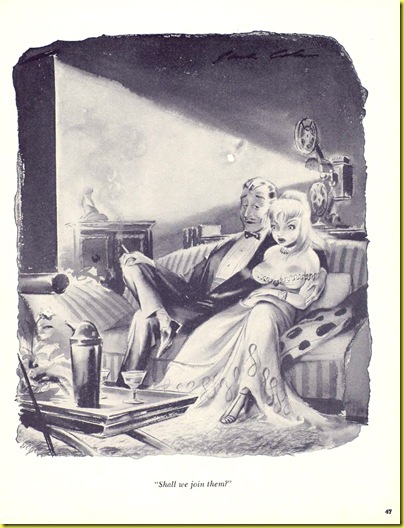

The pattern has now been established where Cole has at least one full-page cartoon and a Females By Cole entry. Just in passing, note the use of patterns again in the next cartoon, below.

Playboy, January 1955

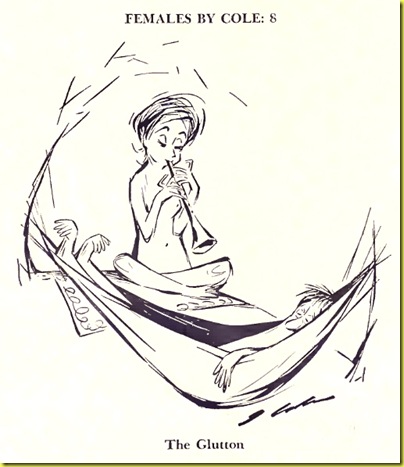

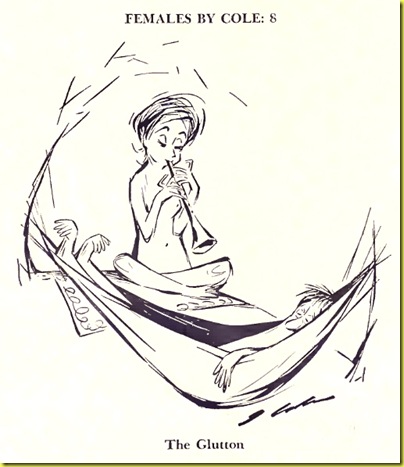

Females by Cole: 8

Playboy, January 1955

Note how Cole suggests a tree with a few scant lines, and a turban with the woman’s hair. The horn points directly at what the woman wants, and the fact that it’s a phallic symbol in her mouth doesn’t hurt the joke, either. Visual wit.

In the February, 1955 issue, Jack Cole only had one cartoon… an anomaly. He re-uses the horizontal format he’s created. Again, there are two jokes.. the hatch marks keeping track of her lovers, and the sexually suggestive pencil sharpener.

In the February, 1955 issue, Jack Cole only had one cartoon… an anomaly. He re-uses the horizontal format he’s created. Again, there are two jokes.. the hatch marks keeping track of her lovers, and the sexually suggestive pencil sharpener.

Females by Cole: 9

Playboy, February 1955

Cole had nothing in the March, 1955 issue. The April, 1955 issue featured his second full-color cartoon:

Playboy, April 1955

Cole made up for his absence in the previous issue with a second cartoon.

Playboy, April 1955

In the two cartoons above, Cole has changed direction. This reworking of his approach may account for the low production of the previous months. Perhaps Hefner requested a new direction. Instead of wimpy men, these two are virile, sexual predators… probably the type of man most Playboy readers fantasized about being, on some level. In the second cartoon, the woman is even shocked by the man’s brazenness, a reversal of Cole’s formula.

Cole’s first year at Playboy rounds out with his tenth FEMALES cartoon:

Females by Cole: 10

Playboy, April 1955

In his first year at Playboy, Jack Cole published 26 witty, funny, and artistically accomplished cartoons. he established himself as the star cartoonist of a new magazine that would drive a cultural phenomenon in America. Unlike Harvey Kurtzman, who also left comics to work with Hugh Hefner (after Cole died), Cole’s work rose to new levels of relevance and had a deep impact on American culture.

The next article in this series will look at Cole’s middle years at Playboy, when he created some of his best-known cartoons and matured to become, in his own ambitious words, one the “best damn cartoonists” ever.

- Text copyright 2010 Paul Tumey.