It is believed that Jack Cole began his cartooning career with a 1935 sale to Boy’s Life magazine. In a wonderful, but somewhat slanted autobiographical piece that Cole published in a 1956 issue of the Freelancer magazine (Issue #2), he recounted this momentous event:

“…I had taken a job with the American Can Company and was well on my way to the normal life when one of my idle-hour etchings made a sale to “Boy’s Life” magazine in 1935.”

Here’s the whole wonderful article (thanks to Harry Green, who recently published the page (courtesy of David Miller, who provided the scans) on his wonderful comic blog, Hairy Green Eyeball 2, and to loyal reader and supporter of this blog, Daniel McKiernan, who made me aware of the post.

Just a few thoughts about this new find. Notice how Cole glosses over the major effort of his life, his 16-year career in comic books. Also, the “minor class magazines” that Cole mentions are the Humorama line (Joker, etc.). A nice collection of these cartoons were collected in The Classic Pin-Up Art of Jack Cole, by Alex Chun. A few of these cartoons can be viewed at this link.

“Cole’s first professional sale, to Boy’s Life in 1935, recounts his 1932 adventure bicycling all across America and back.” (p. 10)

I am a huge fan of Art Spiegelman’s work, but recent scholarship on my part suggests this is incorrect; very likely a mistaken assumption. The first sale to Boy’s Life was not this article, but very likely a one-panel gag cartoon.

Spiegelman was recently kind enough share with me that he got the reproduction of the article’s first page from Cole’s brother, Dick Cole, who had no date information. I think it was a reasonable assumption to make that this article was Jack Cole’s first professional sale. Boy’s Life published articles of this ilk, and in the early 1950’s, I even found a very similar (if much less well written) article in which a teenager tells the story of his west-to-east journey across America by bike, even hitting some of the same out-of-the-way towns as Cole!

However, after searching through Boy’s Life magazine back issues for 1935, I can find no trace of anything by Jack Cole. Not the bike trip article, nor a cartoon or illustration. Nothing. I looked through every page of every issue five times.

In fact, I looked through every page of every issue of Boy’s Life from 1933 to 1941, and I did not find Cole’s “A Boy and His Bike” article. So where was this article published, and when? It’s a mystery, as of this date. My friend and fellow comics curator, Frank Young (see Stanley Stories, his superb and groundbreaking blog on John Stanley) suggests that perhaps the article appeared in his hometown newspaper, the New Castle News (which, unfortunately has no archive for these years). Frank says that the article looks to him like the typical layout of Sunday newspaper rotogravure magazines of the time. Indeed, the layout of this page doesn’t look anything like the layouts Boy’s Life used, although the fonts are similar.

In any case, although Jim Steranko, Ron Goulart, and Art Speigelman, as well as Jack Cole himself all state that Cole’s first professional sale was to Boy’s Life in 1935, I can find no trace of a cartoon in those pages. The first Jack Cole cartoon I have located appears in 1936, not 1935. Could it be that Cole simply mis-remembered? Heaven knows that if you asked me the date of my first fiction sale (“Toy Chest River,” in a hardcover anthology called Christmas Forever), I would very likely get the date a year or two off – and that was a major event for me.

The first issue of Boy’s Life in which Cole’s work appears in is the October issue of 1936. Cole had two cartoons in that issue. It’s possible these represent his first professional sales (I am not sure where the “circa 1934” cartoon shown caption-less in the above Freelancer article comes from. That could be the first sale, or it may even be a rejected cartoon Cole dug out for this piece.)

Boy’s Life (October, 1936)

From the start, Cole is displaying technical prowess with wash and watercolor. 14 years later, his Humorama and Playboy cartoons would in part be so successful because of Cole’s mastery of watercolor.

If I haven’t missed anything in my search, Cole did not place another cartoon in Boy’s Life for 11 months. During this time, he borrowed 500 dollars from his hometown merchants and moved to New York City with his wife Dorothy. By the time his next Boy’s Life cartoon appeared, Cole had begun his comic book career, finding a salaried job at the Harry “A” Chesler studio, the first packager of original comic book material. Talk about being in the right place at the right time -- Cole got in at the ground floor of the development of a whole new art form and branch of publishing!

Boy’s Life (September, 1937)

A typically wacky Jack Cole invention. Cole’s work is filled with surreal inventions such as this one. Compare to the story of the invisible “Flit” spray in Plastic Man #1

Cole had a second cartoon in this issue, as well…

Cole was particularly creative in his next cartoon, creating an irregularly-shaped cartoon cleverly designed to slot into the magazine’s 3-column layout:

Boy’s Life (October, 1937)

Cole’s inspired design supports the subject of the gag very well…

Boy’s Life (November, 1937)

More surrealism. The sort of play with reality that we see a lot of in Cole’s Burp the Twerp one-pagers….

Boy’s Life (December, 1937)

Here we see similar motion and energy that Cole invested in his Plastic Man stories.

Boy’s Life (January, 1938)

Cole’s first published hillbilly cartoon (and a funny one, at that). Hillbilly humor and rural settings are a staple of Cole’s work. See The Highgrass Twins (1940) for starters

Cole had a second cartoon in the Jan 1938 issue… delightfully surreal and again with the invention theme…

Boy’s Life (February, 1938)

Note the use of pure wash effects with no defining border lines… a characteristic of Cole’s stunning 1950’s Playboy cartoons.

Boy’s Life (May, 1938)

Funny drawings…

Note in the above cartoon that Cole’s signature has begun to evolve from the ornate, labored anchor-shaped icon/logo he designed in the earliest cartoons to a more simpler and assured signature. A study of the development of Cole’s signature in his 1936-40 Boy’s Life gag cartoons reveals a march toward simplicity and grace.

The last signatures in this progression are very close to the signature Cole used for his famous Playboy cartoons, some 14 years later.

Boy’s Life (July, 1938)

Impotence was a theme Cole explored in both is comic book, gag cartoons, and in his syndicated comic strip, Betsy and Me.

Boy’s Life (August, 1938)

Boy’s Life (September, 1938)

Only Cole could think of an impossible gag like this… and make it work.

Boy’s Life (January, 1939)

Cole’s visual style is evolving from the “puppet” figure shapes to more organic and flowing forms. You can feel the fluidity of Plastic Man in this image…

Interestingly, a cartoon by Fred Schwab appears in this issue, as well. Schwab worked with Cole at the Chesler studio, and I get the sense they were chums. When asked about the Cole-Schwab connection, Art Spiegelman kindly shared the following information: “Cole really got along well with Fred Schwab since they shared an affinity for screwball Smokey Stover cartooning. I interviewed him for the book (he worked in production at the NYT, but turned out to be an affable man with almost no specific memories.” I suspect that Cole probably helped Schwab get this sale to Boy’s Life.

Boy’s Life (January, 1939)

Boy’s Life (February, 1939)

Ah, an “Eat at Joe’s” cartoon by Jack Cole. That’s like finding a “Kilroy was here” cartoon by Harvey Kurtzman. Notice how effectively Cole has begun to use patterns to create a more richer visual experience. His comic book stories are filled with patterns, such as Woozy Wink’s polka-dotted blouse.

Boy’s Life (May, 1939)

Fred Schwab placed two more cartoons in this issue. These are the last of the Schwab cartoons in Boy’s Life.

Boy’s Life (April, 1939)

To borrow Jeet Heer’s great phrase, the comedy of locomotion…

Boy’s Life (June, 1939)

Cole is becoming more confident and accomplished visually. It is interesting to compare this evolving painterly technique to his still-crude pen-and-ink line work in his 1939-40 comic book stories…

Boy’s Life (September, 1939)

Wow.. look at the motion and the sense of a moment captured in time. Cole has found the underlying mechanism of the visual expression of time and space, and has invented a way to stuff a captured moment with the implied events that occur just before and after the moment, adding enormous depth and profundity to his work. Compare this to the similar waterfall gag of October, 1937 and you will see how much Cole has grown in a very short time. The legendary bluesman Robert Johnson is rumored to have made a deal with the devil to suddenly transform into a master of the guitar. Did Cole make a similar deal in 1939 to acquire the ability to manipulate time and motion in comic book images like no other artist before or since? His growth in this period is uncanny and unexplainable. By the way, this was the largest cartoon I saw in 10 years of Boy’s Life.

Boy’s Life (November, 1939)

Boy’s Life (December, 1939)

Another impressive motion-on-paper moment, and a funny gag, too… almost iconic… just when you think you’re bad off…. there’s a cactus that’s waiting to break your fall….

Boy’s Life (January, 1940)

This gag reminds me of Death Patrol… look at those gorgeous speed lines… Cole has clearly become fascinated with showing motion on paper…

Boy’s Life (June, 1939)

Motion, motion, motion – funny, funny, funny. Cole is now by far the most distinctive stylist of the cartoonists in this run of Boy’s Life. His cartoons leap off the page.

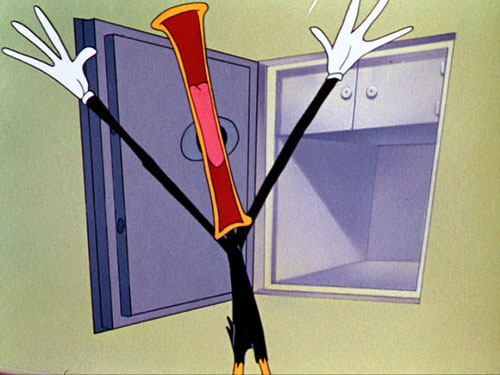

Boy’s Life (October, 1940)

And then, it ends… sadly, here is the last of Cole’s marvelous cartoons for Boy’s Life. In New York City, Cole had taken on the job of editor for Lev Gleason, and devoted himself wholly to comic books for the next 14 years. Look at how this lovely cartoon leaps off the page…

Tuba or not tuba, that is the question…This is the only cartoon in the Boy’s Life panoply that has no caption. Cole has graduated to a “pure” form of gag cartooning with this last entry.

Overall, Cole’s heretofore unseen and unknown Boy’s Life cartoons are a revelation. We can see, more clearly than in his comic book work of the same period, his meteoric growth as a cartoonist.

Somewhere out there, a 4-CD bootleg of Bob Dylan’s unreleased 1962 songs exists, Dylan 1962. Listening to this CD, one can hear in a few tracks the “wild, thin mercury sound” of Dylan’s famous albums of a few years later. The tracks totally undermine the story of Dylan’s artistic development as an acoustic folksinger into an artist who suddenly picked up an electric guitar in 1965. He had the electric sound in 1962, and brought out this new style when it best suited his career.

Similarly, Cole had developed his wash/watercolor gag, compressed-time gag cartoon approach some 15 years prior to his landmark work for Playboy magazine, starting in 1954.

All text is copyright 2011 Paul Tumey