Story this post:

”Plastic Man - Wanted Dead or Alive”

Story and art by Jack Cole

Police Comics #95 (October, 1949 – Quality Comics)

Building on his amazing comic book story in Police #94 (to read, see here), Jack Cole delivers another 11-page knock-out. It boggles my mind that these stories haven’t seen the light of day since their original publication, nearly 60 years ago.

As with most comics in the late 1940’s, the page count of Police Comics dropped a 16-page signature taking a 52-page book down to 36 pages. As a result, the lead Plastic Man stories shrunk from 15 to 11 pages. This was not necessarily a bad thing.

In fact, I suspect the more manageable page count re-opened the series for Cole’s full-scale involvement, effectively taking away a third of the labor that had been required to produce a a four-color adventure of the stretchy sleuth and his rotund Watson. As a result, he was able to enjoy a last stint of producing stories more or less singlehandedly, in the organic method he used in the first half of his comic book career.

All of a sudden, the stories are tighter, have more bite, display about 5 times as much great ideas, and --- best of all – Jack Cole’s talent is at the helm again. Granted, the stories often sink into barely disguised despair, but even then the triumph of Cole’s mastery is astounding to behold, much like listening to a haunting blues song by Robert Johnson… you have to ask yourself “from what otherworldly place did this stuff come?”

In Cole’s last golden period of creating his 35 or so Plastic Man stories that appeared sporadically in the 1948-50 issues of Police Comics and Plastic Man, he accomplished some of the oddest, most unique comic book stories ever made, in my opinion.

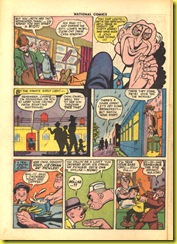

In this story from Police Comics #95, Cole moves out of the shadows of the last story, in which Plas was very nearly executed for murder into an exercise in seeing how far over-the-top he can go in creating bizarre characters. First and foremost amongst the vast array of grotesque villains is Scowls, a fat midget who dresses in a Mickey Mouse tie and is always drawn with a sparkle on his gleaming bald head.

Cover by Jack Cole and Alex Kotzky

Jack Cole liked drawing bear traps. In Police Comics #22 (1943), he killed off a child abusing crook with a bear trap:

His use of the bear trap to snip at Scowls’ fanny in the splash page of this mini-masterpiece is less dark, but equally as compelling.

Overall, it is Cole’s compositions within each panel that are the star feature of this story. He crowds his panels with 5, 10, 15, even 20 figures. Each one is a real person, with real behavior. In the first panel on page three, for example, Cole draws no less than 11 individual people, all preoccupied in their own, comical way, including the great touch of having one crook pick the pocket of another.

No attention is drawn to this gag, and no further elaboration is made of it. The story does not depend on it. It’s merely there as an extra layer of entertainment. There are at least a dozen of these ‘extras’ in this one story alone. In this aspect, Jack Cole’s work prefigures the famous “chicken fat” style of Will Elder’s Mad and Panic stories that would appear in just few short years later, which were loaded with little gags, puns, and surreal jokes that were completely separate from the plot. This device can also be traced back to the great screwball comic newspaper comic strips, particularly SMOKEY STOVER buy Bill Holman (for an article on on Holman’s influence on Jack Cole, see here). To my knowledge, this link has not been observed, or studied much at all.

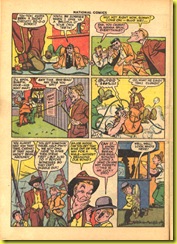

Earlier, I described the extremely bizarre character design of Scowls. His associate, McGoon, is also quite strange, with his elongated torso and total lack of a lower jaw, not to mention the enigmatic “T” shirt he wears. There’s also a crook with a studded metal skull cap, and even a crook with a vaudevillian oversized old-fashioned suit. All of these character designs appeared in earlier Jack Cole stories. Cole is recycling a bit, here.

What makes this story a bit of a tour de force is that, where Jack Cole’s old Plastic Man formula was to feature just one grotesque, Dick Tracy-like villain, here he depicts a whole GANG of bizarre characters.

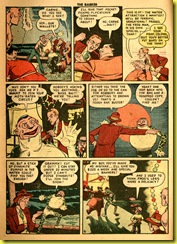

It’s as though every individual in the story has been shaped by some mysterious force into a weird form of themselves, and then frozen in that form. The only fluid person in the story is Plastic Man. It’s his ability to change and flow like water around the obstacles that makes him superior, and completely deflates the threat of being trapped in an air-tight room deep underground loaded with murderous crooks wielding an arsenal of deadly weapons.

At the end, a wholly amused Woozy brags on Plastic Man, actually explaining to us the importance of being able to change:

“Plas always springs the traps and drags the bait away to the big house.”

To underscore this story, similar to the Donald Duck and Uncle Scrooge stories that Carl Barks (Cole’s fellow satirist working in comics) was creating around the same time, Cole creates the character of the horse-grinned, foppish, limp-wristed, dandy who was formerly a criminal mastermind. It was his ability to change that gave him his freedom, even though he changed into just another ridiculous caricature.

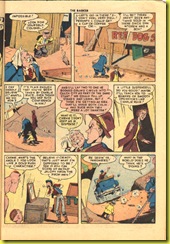

While the writing in this story is good, it the wholly realized visual art that takes center stage in this adventure. Each panel is a picture that can truly stand on it’s own both compositionally, and as a powerful image in itself. I’ll leave you with a little gallery of three examples of many worth admiring from this exemplary, strange dark late comic book story by the great Jack Cole: