The master of all things comic book and horrorific, Steve Karswell, has posted "The Brain That Wouldn't Die" from Web of Evil #10 (January, 1954) at his always-fun blog, The Horrors Of It All.

This is a key Jack Cole story. It was one of his very last comic book stories, and was published as his second-to-last story (for his final published comic book story, see my post on "I Was The Monster They Couldn't Kill" here).

You can read "The Brain That Wouldn't Die" at Karswell's blog by clicking here.

Firstly, there may be a question in some readers' minds as to whether this story actually is by Jack Cole. The Grand Comics Database currently lists the story as being by John Forte (they credit another story in Web of Evil #10 to Cole, "Death's Highway," which is not his work. Karswell has published that story on extensive blog as well, and you can read it by clicking here.)

Firstly, there may be a question in some readers' minds as to whether this story actually is by Jack Cole. The Grand Comics Database currently lists the story as being by John Forte (they credit another story in Web of Evil #10 to Cole, "Death's Highway," which is not his work. Karswell has published that story on extensive blog as well, and you can read it by clicking here.)I feel certain this story was written and penciled by Jack Cole. It is very much "of a piece" with the rest of his Web of Evil work. The title alone is similar to Cole's story from Web of Evil #1, "The Corpse That Wouldn't Die."

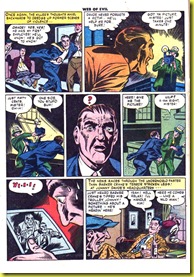

There are a number of "Cole-isms" in this story that indicate Cole's work, as well. These include Cole's characteristic sound effects lettering, as we see in this panel from the story (which, by the way, could also serve as a panel from any of his lurid True Crime stories):

Then there's the pervasive scenes of dread and anxiety. I think Cole was channeling Cold War nuclear fear. He went very, very dark at the end of his career. Even in Plastic Man. See my post on "Dark Plas" by clicking here.

Lastly, there is the sense of movement in several of the panels. Check out this psycho-sexual portrait of speed and obsession:

The writing is by whoever else wrote the bulk of the Web of Evil stories Cole drew -- whether it's him or someone else. This story has the same dynamic between the twisted, broken individual who is at odds with society as several of the others, such as "Monster of the Mist," and "Killer From Saturn."

The 16 Web of Evil stories that Jack Cole drew fall into two types: Unexplained Supernatural Events and Psychological Breakdowns. It seems to me that Jack Cole may have written wrote the stories that fall into the latter category, if not all of them.

The Man Who Died Twice (Web of Evil #5)

Orgy of Death (Web of Evil #6)

The Spectre’s Face (Web of Evil #6)

Death Prowls the Streets (Web of Evil #8)

A Pact With The Devil (Web of Evil #9)

I Was The Monster They Couldn’t Kill (Web of Evil #11)

What gives "The Brain That Wouldn't Die" depth beyond the standard comic book horror story is the way Cole's imagery encourages us to consider the story as a metaphor for the self. It raises Phil Dickian questions about reality and what it means to be human. Is a brain in a jar a human being?

Jack Cole’s Web of Evil stories pulled the title out of a standard horror realm, and stretched the series into crime and science fiction as well. Instead of a horror story, Cole would write a crime story as if it were a horror story, playing with reader expectations.

"The Brain That Wouldn't Die" as most readers will know, is the title of a very similar movie released in 1962. One wonders if Cole's horrific brain-in-a-jar imagery in this story inspired them.

Another interesting aspect to this story is that it is about a crazy inventor. From his 1939 "Dickie Dean" stories onward, Jack Cole populated his comic book work with brilliant, and often cracked, inventors. It's an archetype that Cole -- an inventor himself -- identified with, I think.

It's also worth noting that the inventor character in "The Brain That Wouldn't Die," Dr. Renard, is a Cold War version of Cole's longest-running inventor character, Doc Wackey, from his 40 or so Midnight stories published in Smash Comics. Physically, they are dead-ringers for each other:

The story ends perfectly, with the wildly protesting "talking" brain casually dropped into an incinerator to be destroyed. Is this how Jack Cole, after beating his brains out for 16 years in comic books felt?

The surname of the main character in "The Brain That Wouldn't Die," Renard, is a French-German name that means "strong decision." Perhaps Cole's choice of the name, "Renard," was, consciously or not, an indication that he was making his own strong decision to leave comic books, Plastic Man, and Woozy behind.

By the time this story was published, Cole had left Quality Comics. After that, the only work in comics he found was touching up stories for post-code publication as an assistant to Marc Swayze at Charlton Comics in Derby Connecticut. That's a little like hiring Ernest Hemmingway to write supermarket signs. No wonder Cole left after three weeks, never to work in the comic book industry again.

I am totally psyched to see this story appear here. Thanks, Karswell!

Note: The Grand Comics Database, which I love, has a few errors around Cole's work, which is understandable since a clear understanding of the different phases of his work is only just now coming into focus. I am working as an indexer/error tracker at that site to correct the errors, but it is a slow process. I'll add this correction to my list!

All text copyright 2012 Paul Tumey